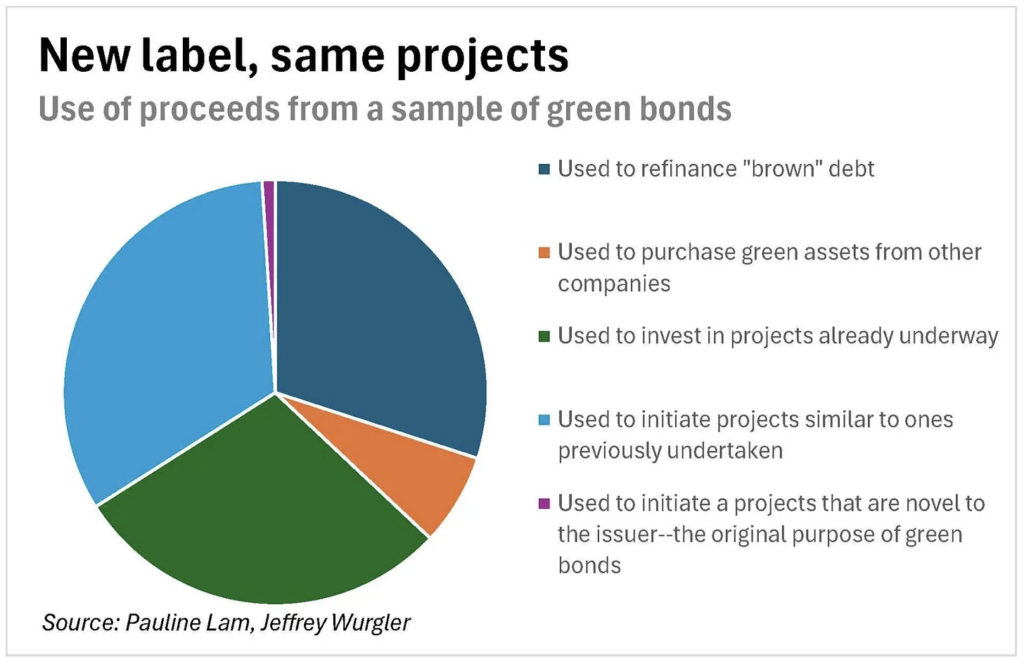

Less than 1% of green bond proceeds used for green projects

This column first ran on Callaway Climate Insights.

A new study finds that green bonds have done virtually nothing to make the world greener.

The study, titled “Green Bonds: New Name, Same Projects,” was conducted by Pauline Lam, a visiting scholar at NYU’s Stern School of Business, and Jeffrey Wurgler, a finance professor at that institution. Their research is being presented May 17 at a University of Chicago conference.

Heat Problems –April Sets A Record

Climate News –Chocolate Gets More Expensive

The researchers’ conclusion is profoundly depressing because green bonds originally held such promise.

They were to channel a new source of funds for companies to pursue environmentally friendly projects that they otherwise might not have been able to pursue. If the bonds had lived up to their promise, the more than $2.6 trillion of green bonds issued over the last decade therefore could have gone a long way towards helping companies mitigate climate change.

Prior to this new study, most research on green bonds focused on measuring the difference in yields between green and “brown” bonds — the so-called greenium. The consensus of those prior studies was that the greenium is either nonexistent or so small as to be irrelevant. But those studies were unable to understand why this is so.

Lam and Wurgler dug much deeper than those prior studies, analyzing the actual uses to which green bond issuers put the proceeds. They were looking for instances in which the proceeds were actually used to pursue green projects that were indeed novel relative to what the issuer had already been doing using traditional financing sources.

To search for this “additionality,” the researchers engaged in a painstaking analysis of multiple sources, including the bonds’ offering prospecti, SEC documents, internal company reports, and direct correspondence with the companies. They focused on a sample of both corporate and municipal green bonds that were chosen to maximize the possibility of finding additionality. They nevertheless found next to none.

In their sample of corporate green bonds, they found that:

- 30% of proceeds went to simply refinance preexisting brown bonds;

- 7% went to purchasing green assets from other companies (which of course results in no net “societal increase in green assets”);

- 29% of proceeds were invested in projects that were already underway prior to the issuer’s first green bond issue;

- 33% of proceeds were used to initiate projects similar to others that the company had previously undertaken, prior to issuing any green bonds;

- 1% of proceeds were used “to initiate a project whose green aspect is novel for the issuer”

Only this latter category, representing just 1% of proceeds — or, to be charitably exact, 1.4% — represents true additionality over business as usual, according to the researchers. (They reached similar results when analyzing their sample of municipal green bonds.)

It is tempting to interpret these results as yet more evidence of companies cynically wrapping themselves in a green flag — greenwashing, in other words.

But that is only half the story, Wurgler said in an interview. Investors themselves share the blame with the companies, since the absence of any significant greenium indicates that they are unwilling to accept a lower interest rate on green bonds in order to incentivize companies to do more than they would otherwise. It’s therefore unfair to blame just the companies for not creating green projects that represent true additionality.

There’s plenty of blame to go around, of course. A perhaps more charitable interpretation is that the green bond market’s true potential has not yet been exploited. Its failure over the past decade doesn’t represent an inherent defect, but instead an unwillingness to actually use its unique form of financing.

Both companies and investors will have to take some risks if green bonds are to have any chance of living up to their potential.

On the one hand, environmentally concerned investors will have to be willing to forfeit at least some return if they want to incentivize companies to undertake green projects that they wouldn’t have otherwise been willing to pursue. On the other hand, companies must be willing to inaugurate such projects even before financing is secured, and then engage in aggressive marketing of those projects to attract enough investors who are willing to accept a lower green bond yield.

One thing, however, is certain: As currently constituted, the green bond market won’t be helping to overcome the climate crisis.

Sponsor

Find a Vetted Financial Advisor

- Finding a fiduciary financial advisor doesn't have to be hard. SmartAsset's free tool matches you with up to 3 financial advisors that serve your area in 5 minutes.

- Each advisor has been vetted by SmartAsset and is held to a fiduciary standard to act in your best interests. Get on the path toward achieving your financial goals!