Climate Change May Transform These Wine Regions By 2080

Since the Industrial Revolution, the United States has warmed by roughly 2°F. As temperatures rise, climate change is reshaping coastlines, forests, and grasslands, shifting biomes and forever altering the U.S. agricultural landscape.

Wine grapes are among the most climate-sensitive crops on Earth. A slight shift in temperature or moisture can alter ripening cycles, sugar levels, and the flavor chemistry that defines a region’s terroir. As global warming pushes biomes northward, upslope, or into entirely new ecological zones, growing conditions in dozens of America’s federally-recognized wine regions – known as American Viticultural Areas, or AVAs – may be fundamentally different than those that shaped their identity.

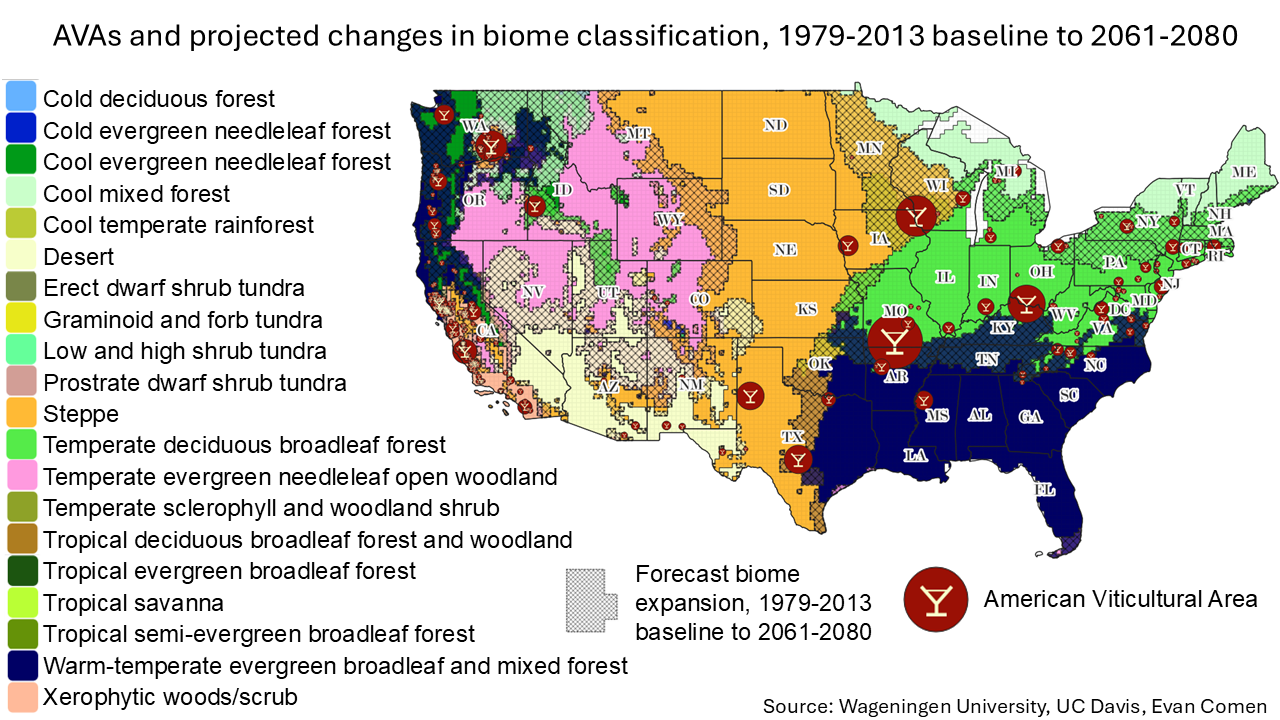

A 2023 study published in PeerJ by the Open-Earth-Monitor Cyberinfrastructure project used high-resolution climate and vegetation data to model how global biome zones will shift by 2080 under a high-emissions scenario. Their projections show that many AVAs will no longer share the same dominant biome type by mid-century. Forecast biome changes could disrupt everything from varietal suitability and yield stability to wildfire risk, water availability, and the broader cultural identity of iconic wine regions.

Pinot-driven regions like the Willamette Valley, traditionally cool and forested, are projected to resemble parts of Northern California, while high-altitude zones like Grand Valley in Colorado may transition into true desert landscapes. In many cases, future biomes look hotter, drier, and less grape-friendly than the one that exists today. A closer look at the data reveals the wine regions facing the most dramatic transformations by 2080.

To identify the AVAs most at risk from biome shifts, Climate Crisis 247 analyzed spatial data from the PeerJ study and overlaid it with the boundaries of all U.S. AVAs. Each AVA was assigned both a baseline biome classification for 1979-2013 and a forecast biome classification for 2061-2080. AVAs where the dominant biome is projected to change were ranked by the magnitude of that shift – measured as the distance between the baseline and projected vegetation classes in the BIOME 6000 classification scheme. Only AVAs at least 100 square miles in size with a full biome transition were included.

22. Wahluke Slope (Washington)

Wahluke Slope is one of Washington’s warmest AVAs, defined by low rainfall, sandy soils, and high-yielding red varietals like Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot. Currently, it occupies a temperate evergreen needleleaf open woodland biome, a dry but semi-forested transition zone that still benefits from Columbia Basin irrigation and cooling evening winds.

Climate projections suggest a shift to a true desert biome by 2080, marking sharper declines in natural moisture and greater reliance on groundwater and snowpack runoff. As the region becomes hotter and drier, sugar accumulation may outpace phenolic ripeness, forcing winemakers to reconsider canopy management, shade strategies, and potentially the long-term viability of some Bordeaux varieties.

21. Crest of the Blue Ridge Henderson County (North Carolina)

This young Appalachian AVA sits at elevation along the Eastern Continental Divide, anchored today in a temperate deciduous broadleaf forest biome with cool nights, heavy rainfall, and acidic mountain soils well-suited to Chardonnay, Cabernet Franc, and sparkling wine production. High-altitude vineyards have so far provided natural protection from extreme heat.

By 2080, the region is projected to move into a warm-temperate evergreen broadleaf and mixed forest biome, a sign of rising minimum temperatures and shorter cool seasons. That shift could reduce acidity, hasten ripening, and force growers to pivot from cool-climate styles toward fuller-bodied reds or heat-adapted hybrids more common in the Southeast.

20. Upper Hiwassee Highlands (Georgia & North Carolina)

Straddling the southern Appalachians, the Upper Hiwassee Highlands AVA is rooted in a temperate deciduous broadleaf forest biome, where cooler mountain air, high rainfall, and clay-loam soils support hybrids and early-ripening vinifera such as Seyval Blanc, Chambourcin, and Cabernet Franc.

By 2080, the region is projected to shift into a warm-temperate evergreen broadleaf and mixed forest biome, signaling hotter summers and more subtropical conditions. Such warming may reduce the viability of cool-climate varieties, move harvests earlier into hurricane season, and increase disease pressure – potentially pushing growers toward Muscadines, heat-tolerant hybrids, or Southern Rhône–style plantings.

19. Rogue Valley (Oregon)

Rogue Valley, Oregon’s southernmost AVA, hosts a wide range of microclimates, from cool river valleys to warm, high-sun slopes. Today it sits within a cool evergreen needleleaf forest biome, where conifers and altitude help moderate summer heat and support structured reds like Syrah and Cabernet Sauvignon along with Pinot Noir at higher elevations.

By 2080, the biome is forecast to transition into a warm-temperate evergreen broadleaf and mixed forest, resembling parts of inland California more than current-day Oregon. Longer, hotter growing seasons could increase drought stress and wildfire risk, favoring Rhône and Mediterranean varietals over Pinot Noir and forcing a redefinition of the region’s stylistic center.

18. Clements Hills (California)

Part of the broader Lodi AVA, Clements Hills lies in a warm interior valley marked by rolling hills, decomposed granite soils, and a xerophytic woods and scrub biome, well-suited to Zinfandel and other high-brix varieties. Its arid climate already demands careful water management.

Desertification is forecast to continue into 2080 as the region shifts into a steppe biome, a move toward hotter, drier conditions with less natural vegetation cover. Increased heat load and water scarcity may push some vineyards toward drought-resilient rootstocks, shade cloths, or even reduced acreage – while simultaneously improving ripeness for heat-loving Spanish and Portuguese varietals.

17. Grand Valley (Colorado)

Nestled along the Colorado River at 4,500 feet, Grand Valley is one of the highest-elevation wine regions in the U.S. Grand Valley is currently classified as a temperate evergreen needleleaf open woodland biome, where high diurnal swings, sandy soils, and cold winters help balance ripeness in Cabernet Franc, Syrah, and aromatic whites.

By 2080, Grand Valley is projected to transition into a desert biome, reflecting reduced snowpack, lower humidity, and hotter summers. That shift could intensify frost risk in winter while accelerating ripening in summer, narrowing the already tight viability window for vinifera and potentially demanding more cold-hardy hybrids or canopy innovations.

16. Paso Robles (California)

Paso Robles spans more than 600,000 acres of rolling oak woodland and scrub, currently classified as a xerophytic woods and scrub biome and known for robust Rhône and Bordeaux reds. Hot days, cool nights, and calcareous soils define the region’s style and agricultural output.

By 2080, the biome is projected to shift to steppe, indicating even drier conditions with less vegetative cover and intensified summer heat. Reduced water availability, declining soil moisture, and higher wildfire volatility may reshape vineyard economics, favoring deep-rooted, drought-tolerant varieties and potentially limiting expansion in some sub-AVAs.

15. Applegate Valley (Oregon)

South of the Rogue River, Applegate Valley is currently situated in a cool evergreen needleleaf forest biome, where mountain elevation combines with warm, dry summers. The biome supports both Bordeaux reds and aromatic whites, benefitting from long autumn hang time and moderated heat.

By 2080, the region is expected to enter a warm-temperate evergreen broadleaf and mixed forest biome, transforming into a hotter, more Californian growing environment. Earlier ripening, lower acidity, and increased irrigation demand may shift plantings toward Grenache, Tempranillo, or even Italian varieties suited to semi-arid heat.

14. Upper Hudson (New York)

The Upper Hudson AVA sits on the northern edge of New York’s wine belt, in a cool mixed forest biome dominated by maple, birch, and spruce. Historically marginal for vinifera, the region leans heavily on cold-hardy hybrids like Marquette, La Crescent, and Frontenac.

By 2080, the area is projected to shift into a temperate deciduous broadleaf forest biome, signaling warmer winters and longer growing seasons. The change could finally make select vinifera grapes viable, while also reducing winterkill risk – though hotter summers may introduce new disease and storm pressures.

13. Fredericksburg in the Texas Hill Country (Texas)

Centered around limestone hills west of Austin, Fredericksburg AVA exists today in a warm-temperate evergreen broadleaf and mixed forest biome, where Mediterranean varietals like Mourvèdre, Sangiovese, and Tannat thrive under intense sun and shallow soils.

By 2080, the biome is projected to shift to steppe, indicating a hotter, more drought-prone landscape with declining vegetative cover. Increased heat stress and dwindling water resources may force growers to adopt dry-farming methods, heat-tolerant clones, or even consider desert-adapted varieties such as Assyrtiko or Aragonez.

12. Finger Lakes (New York)

The Finger Lakes AVA, moderated by deep glacial lakes, is rooted in a cool mixed forest biome, ideal for Riesling, Cabernet Franc, and sparkling wine. Cold winters and lake effect cooling currently protect acidity and delay budbreak.

By 2080, the region is forecast to become a temperate deciduous broadleaf forest biome, meaning warmer winters, earlier budburst, and expanded ripening potential. That shift could support red varietals previously limited by climate, but may also reduce the natural acidity that defines Finger Lakes Riesling.

11. Cayuga Lake (New York)

Centered around one of the deepest lakes in North America, Cayuga Lake AVA shares the cool mixed forest biome of the broader region, where moderating lake breezes sustain aromatic whites and méthode traditionnelle sparkling wines.

By 2080, it is projected to move into a temperate deciduous broadleaf forest biome, opening the door to fuller-bodied reds and reducing frost risk, while raising concerns about summer heat spikes, rot pressure, and stylistic shifts away from high-acid wines.

10. Seneca Lake (New York)

Home to the deepest and most thermally stable of the Finger Lakes, Seneca Lake AVA supports some of the coldest-climate vinifera in the country in a cool mixed forest biome. Riesling dominates, with frost-mitigating lake effect and shale soils driving its profile.

By 2080, the shift to a temperate deciduous broadleaf forest biome would lengthen the growing season and widen varietal possibilities – but could also erode the high-acid, mineral-driven style that built the AVA’s reputation.

9. Leelanau Peninsula (Michigan)

Jutting into Lake Michigan, the Leelanau Peninsula AVA lies in a cool mixed forest biome with sandy glacial soils and strong lake influence. Cool summers favor Riesling, Pinot Gris, and sparkling wine.

By 2080, the region is projected to join a temperate deciduous broadleaf forest biome, warming enough to support red vinifera at scale, though higher humidity and storm frequency could complicate disease control and reduce the crisp acidity that defines current production.

8. Clear Lake (California)

Located in Lake County north of Napa, Clear Lake AVA sits today in a cool evergreen needleleaf forest biome, where high elevation, volcanic soils, and afternoon winds help maintain acidity in Cabernet Sauvignon, Sauvignon Blanc, and Petite Sirah. The region’s cooler nights and clean air have made it a rising site for premium reds without Napa prices.

By 2080, the area is projected to shift into a warm-temperate evergreen broadleaf and mixed forest biome, bringing hotter summers, earlier ripening, and greater wildfire exposure. The change may push the region toward riper, denser styles and increase irrigation pressure, potentially favoring Mediterranean grapes over Bordeaux varieties.

7. Paso Robles Estrella District (California)

A sub-AVA of Paso Robles, Estrella District lies in a xerophytic woods and scrub biome, defined by hot summers, limited rainfall, and alluvial soils well-suited to Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah, and Rhône blends. Its warm climate already pushes the upper edge of ripening for some varieties.

By 2080, the district is projected to transition into a steppe biome, a sign of intensified drying, lower natural vegetation, and greater evapotranspiration. As the area becomes more desert-like, vineyard survival will depend increasingly on deep wells, drought-tolerant rootstocks, and canopy shading, reshaping both yield and style.

6. Willamette Valley (Oregon)

The Willamette Valley, the heart of American Pinot Noir, is currently rooted in a cool evergreen needleleaf forest biome, where conifer canopies, maritime air, and long growing seasons define its hallmark balance of acidity and ripeness. Its cool-climate identity underpins the region’s global reputation.

By 2080, the biome is projected to shift to a warm-temperate evergreen broadleaf and mixed forest, resembling today’s northern California foothills more than coastal Oregon. Warmer summers and shorter cool seasons could force a transition away from ultra-cool-climate Pinot Noir and Chardonnay toward Syrah, Tempranillo, or warmer-climate Chardonnay styles, changing the valley’s benchmark profile.

5. El Dorado (California)

High in the Sierra Foothills, El Dorado AVA sits in a cool evergreen needleleaf forest biome, where elevation moderates heat and enables diverse plantings from Barbera to Zinfandel to Rhône reds. Its granite soils and alpine nights have long protected freshness in high-altitude wines.

By 2080, the region is projected to become part of a xerophytic woods and scrub biome, meaning hotter summers, lower soil moisture, and expanded drought stress. The shift could push growers toward hardier Mediterranean varieties and reduced yields, while also elevating wildfire danger throughout the foothills.

4. Columbia Gorge (Oregon & Washington)

The Columbia Gorge AVA spans dramatic elevation gradients along the Columbia River, currently grounded in a cool evergreen needleleaf forest biome on the western side, supporting Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, and aromatic whites. Referred to as a “world of wine in 40 miles,” the Gorge’s reputation reflects rapid climate and soil shifts.

By 2080, models project the region will move into a warm-temperate evergreen broadleaf and mixed forest biome, warming enough to push cool-climate grapes eastward or upslope. The change could expand red wine suitability but compress the remaining cool-climate zones, challenging the Gorge’s diversity-based identity.

3. Puget Sound (Washington)

Puget Sound AVA is one of the coolest and wettest wine regions in the U.S., set in a cool evergreen needleleaf forest biome shaped by marine air, rainfall, and low heat accumulation. It specializes in Siegerrebe, Madeleine Angevine, and sparkling-focused whites rarely grown elsewhere in the country.

By 2080, the biome is projected to shift to warm-temperate evergreen broadleaf and mixed forest, a major thermal jump that may finally allow mainstream vinifera like Pinot Noir and Chardonnay – but at the cost of losing the ultra-cool climate character that currently defines the region’s niche.

2. Trinity Lakes (California)

In the far northern Coast Range, Trinity Lakes AVA lies in a cool evergreen needleleaf forest biome, with high elevation and remote mountain conditions shaping small-scale plantings of Bordeaux reds and Riesling. Snowmelt and forest cover currently regulate growing conditions.

By 2080, the region is projected to transition into a warm-temperate evergreen broadleaf and mixed forest biome, indicating hotter summers, longer drought periods, and reduced snowpack. Heat stress and water scarcity may make traditional European vinifera increasingly difficult to maintain without irrigation expansion.

1. Tualatin Hills (Oregon)

On the northwestern edge of the Willamette Valley, the Tualatin Hills AVA is defined today by a cool, moist evergreen needleleaf forest biome, where long growing seasons favor Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, and other cool-climate grapes. The region’s forested landscape helps preserve acidity and delay ripening.

By 2080, the AVA is projected to shift into a warm-temperate evergreen broadleaf and mixed forest biome, bringing hotter, drier summers and earlier harvests. The change may force a shift toward heat-tolerant varieties and new vineyard practices to maintain balance in wines that built the region’s identity.

Sponsor

Find a Vetted Financial Advisor

- Finding a fiduciary financial advisor doesn't have to be hard. SmartAsset's free tool matches you with up to 3 financial advisors that serve your area in 5 minutes.

- Each advisor has been vetted by SmartAsset and is held to a fiduciary standard to act in your best interests. Get on the path toward achieving your financial goals!

More from ClimateCrisis 247

- Arctic Air May Bring Freezing Temps to These Cities This Weekend

- $100 Million Coal Aid

- Where Americans Will Leave Due To Climate Change

- Bill Gates Says Climate Money Is Wasted