Lack of Infrastructure, Charging ‘Dead Zones’ Hinder EV Adoption in the U.S.

The slow adoption of electric vehicles in the U.S. is one of the largest barriers to reducing American dependence on oil and achieving net zero emissions by 2050. Light-duty vehicles currently account for 17% of all U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, more than the residential and industrial agriculture sectors combined.

While consumer demand for hybrid and electric vehicles is rising steadily – from 12.9% of new car sales in 2022 to 16.3% in 2023 – EVs still account for just about 1% of all registered light-duty vehicles on U.S. roads. In the S-curved model of technology adoption, the EV market is still attempting to cross the “chasm” separating the early adopter enthusiast and the average consumer who just wants a better car.

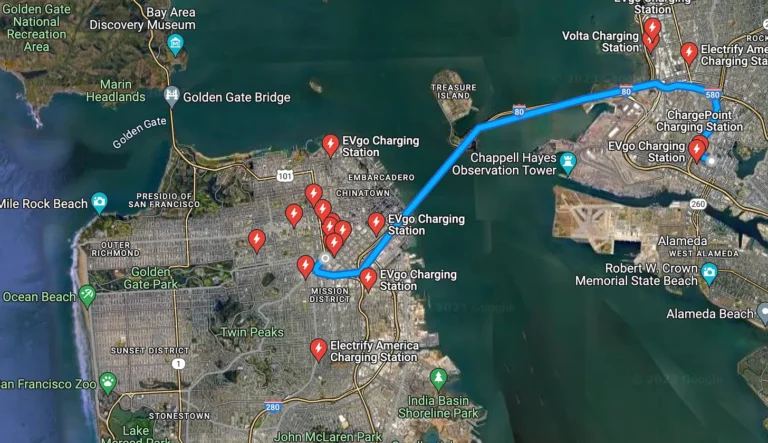

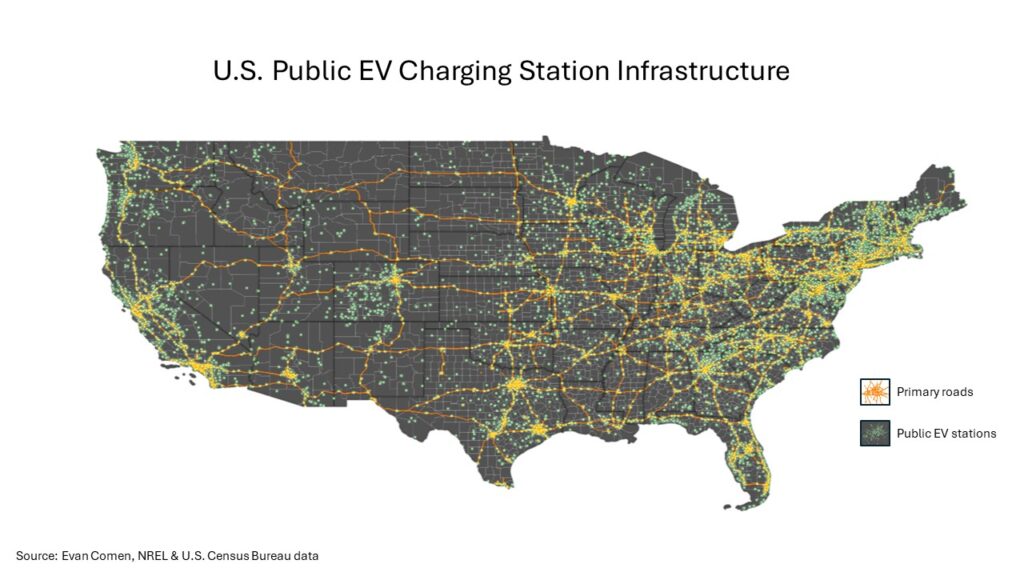

One of the largest barriers to EV adoption in the United States is the lack of charging infrastructure. While there are currently some 67,000 public EV charging stations in the United States, a recent McKinsey analysis estimates that America would need over one million public EV chargers by 2030 to support federal EV adoption targets. Poor infrastructure has created charging “dead zones” throughout the country where consumers may be reluctant to rely on electric vehicles for all of their travel needs. In consumer sentiment surveys, Americans often cite range anxiety and lack of charging infrastructure as the major deterrents to buying electric.

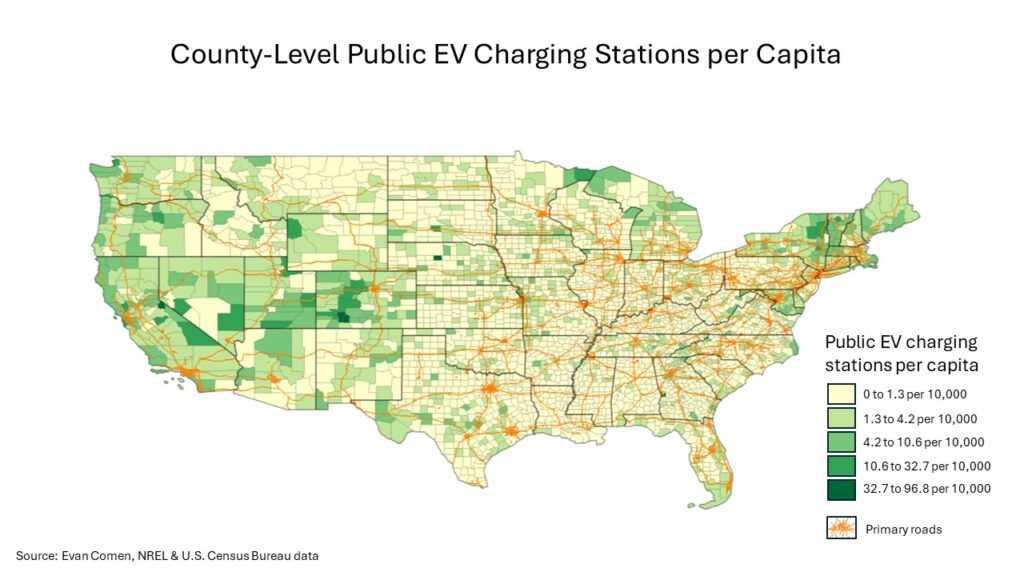

Currently, the lack of charging infrastructure is most pronounced in poor, rural areas. Extrapolating on figures from the McKinsey analysis – 1.2 million EV stations to support a fleet of 48 million cars across a population of 293 million – America would need about 40 public EV chargers per 10,000 residents to meet its electric transition goals. As the map below shows, approximately 4 in 5 counties have fewer than 2 EV charging stations per 10,000 residents.

While some parts of the country – wealthy regions with large tech sectors like the Colorado Front Range, the Champlain Valley in Vermont and New York Adirondacks, and Silicon Valley – are ahead of the curve in EV adoption, huge swaths of the South and Midwest lack the necessary infrastructure to support widespread EV usage. At the county level, an increase in the share of the workforce employed in the tech sector of 2.5 percentage points is associated with an increase of 1 additional EV charging station per 10,000 residents.

At the city level, the West Coast dominates in charging stations per capita, alongside a few standouts in the Midwest and East Coast.

| City | Public EV fueling stations per 10,000 residents |

|---|---|

| Santa Clara, CA | 28.4 |

| South San Francisco, CA | 28.1 |

| Palo Alto, CA | 28.0 |

| Irvine, CA | 21.8 |

| Cambridge, MA | 20.9 |

| Santa Monica, CA | 20.4 |

| Redwood City, CA | 20.0 |

| Bellevue, WA | 18.7 |

| Boulder, CO | 16.8 |

| Cupertino, CA | 15.9 |

| Newport Beach, CA | 13.3 |

| San Mateo, CA | 11.7 |

| Waltham, MA | 11.6 |

| Brookhaven, GA | 11.4 |

| San Rafael, CA | 11.3 |

| Reston, VA | 10.1 |

| Columbia, MD | 9.9 |

| Kansas City, MO | 9.9 |

| Mountain View, CA | 9.6 |

| Costa Mesa, CA | 9.5 |

| East Hartford, CT | 9.4 |

| Arlington, VA | 9.4 |

| Walnut Creek, CA | 9.3 |

| Milpitas, CA | 9.2 |

| Burbank, CA | 9.2 |

While the highest concentrations of EV chargers are in wealthy, educated tech hubs with high EV demand, the buildout of a national charging infrastructure poses a classic chicken-and-egg marketplace problem and may require government intervention. Consumers are reluctant to buy EVs without proper charging infrastructure, while firms are unwilling to invest in EV infrastructure without a robust customer base. With insufficient incentives for firms, state and local governments and private businesses may need federal funds to help complete the national network.

In November 2021, the Biden administration approved $7.5 billion for the building of 500,000 EV chargers by 2030. Due to slow rollout, however, state transportation authorities have built just a handful of new charging stations with the federal funds.

Consumer ambivalence surrounding electric vehicles is still a major roadblock on the route to net zero. While many of the largest automakers have bet big on the green revolution, adding dozens of new EV models to their lineups and spending billions to ramp up production, EVs are starting to pile up on dealer lots, leading to industry concerns over supply glut and bloated inventory. For the industry to continue to grow, state transportation officials need to step on the gas (or electric accelerator pedal), and fast.

Methodology:

To determine the cities and counties with the most EV chargers per capita, 24/7 Climate Crisis reviewed data on alternative fueling station locations from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Cities and counties were ranked based on the number of public electric vehicle charging stations within their boundaries per 10,000 residents as of March 2024. City and county boundaries are from the U.S. Census Bureau and are for 2023. Data on population and median household income are from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2022 American Community Survey and are five-year estimates. Data used to calculate the regression slope in the relationship between information sector employment and public EV charging stations per capita is from the 2022 Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages program of the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

More from ClimateCrisis 247

- Wind And Solar Face Real Damage Under Trump Laws

- Europe Tesla Sales Plunge 40%

- There Are No Cheap Used EVs

- EV Sales Skyrocket, According To Study